Israa Malhouni contributed to this article

Learning does not always happen behind a desk. Surrounded by numerous interactive exhibits and technology, our field trip to the Massachusetts Institution of Technology (MIT) Museum focused less on observing displays and more on critical thinking.

The day began buzzing with energy, as the train filled with excited AP Seminar students as they made their way to MIT. Jumping on the Orange Line from Malden Center to Forest Hills, we walked to Downtown Crossing to switch onto the Red Line at Alewife Station to reach the Kendall/MIT Station.

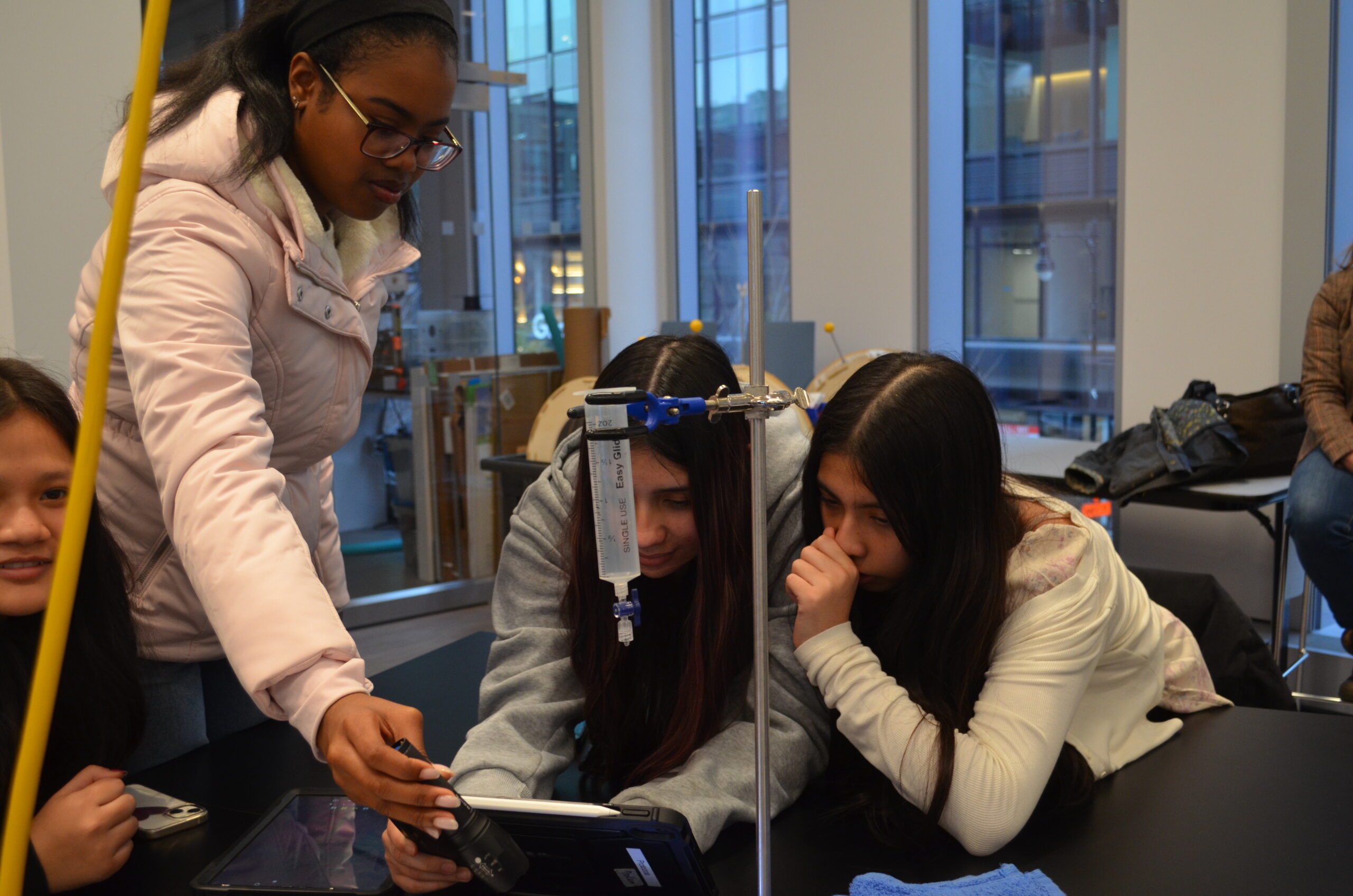

Once we arrived at the museum, we were separated into groups and escorted into the Makers Hub, where we performed a hands-on lab using 3D pens. Each group had the choice to create a structure designed to repel or adhere water, depending on the experiment. Roles were assigned within each table—the designer, photographer, technician, and light operator, so that each group member would play a part.

Once we finished creating our designs, our instructor, and also the Manager of Science Education, Dora Bever, used a high-speed camera to record water interacting with the 3D structures, capturing each droplet as it was either absorbed or adhered to the plant’s surfaces. Watching the process unfold on video brought the experiment to life in a way that reading about it in class never could.

After seeing our 3D creations in action, the excitement continued to brew. Each exhibit we visited afterward was built on the same sense of curiosity and hands-on learning, making it clear that the MIT Museum was designed to challenge the way we think about science and innovation, while engaging the research aspect of AP Seminar.

Our exploration began with a tour of Essential MIT: a gallery dedicated to digital media, technology, space, and innovation, catering to societal improvement by sharing the stories of individuals from around the world. From pursuing “sanitary difference” in Gujarat, India, to highlighting the importance of “biomass cooking” in Uganda to prevent smoke inhalation, to creating the “SurgiBox solution” for first aid, the MIT D-Labs in the exhibit illustrated how the university-based program works with people around the world to develop and advance collaborative approaches and practical solutions to global poverty challenges.

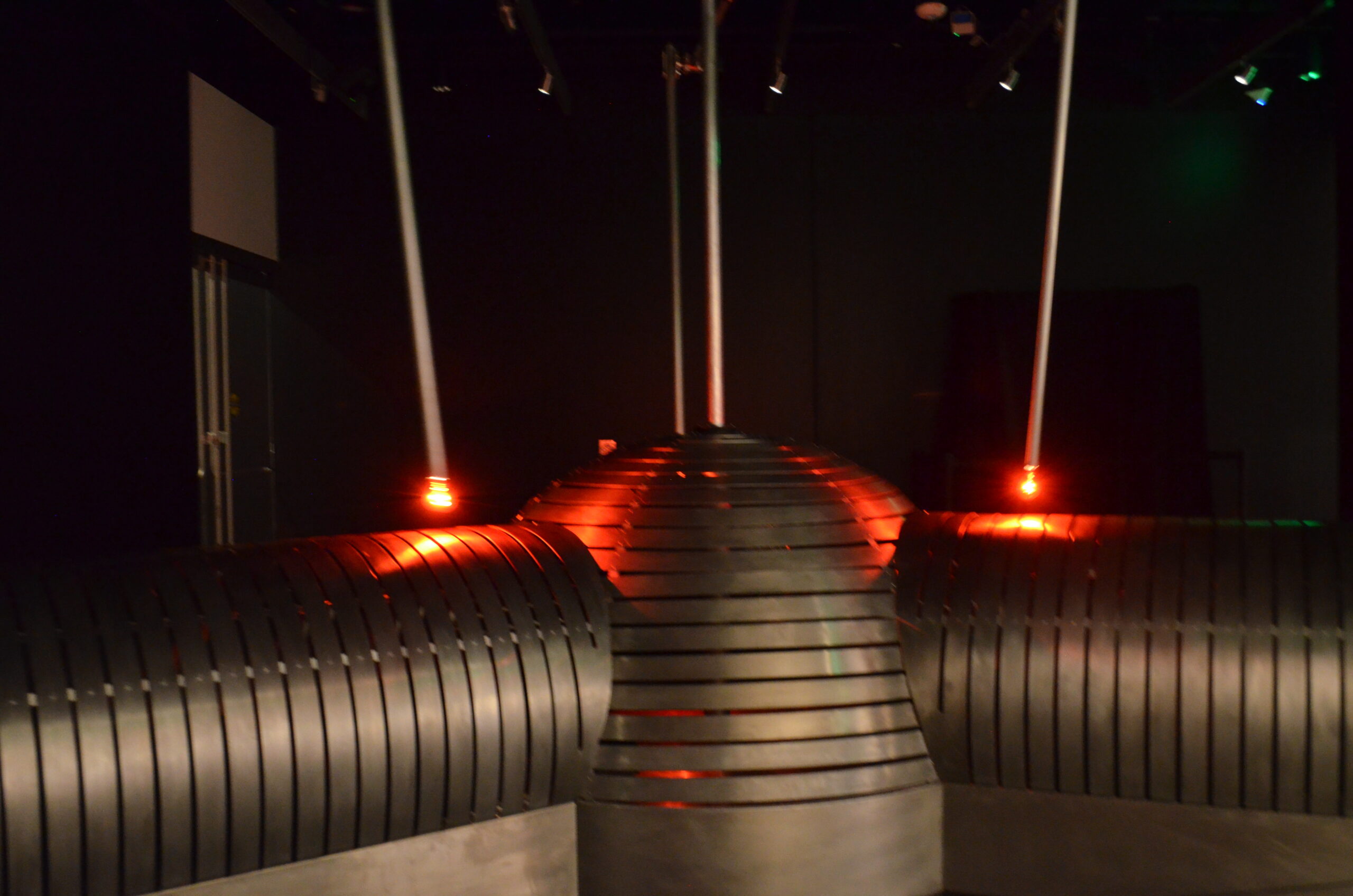

As we took in groundbreaking projects of biotech and space, we moved into an area with dimmed lights called “Lighten Up! On Biology and Time” in the Henri A. Termeer Gallery. By far the most interesting and beautiful, Lighten Up! focused on how circadian rhythms affect our dreams, perception, and health by creating a sensory environment.

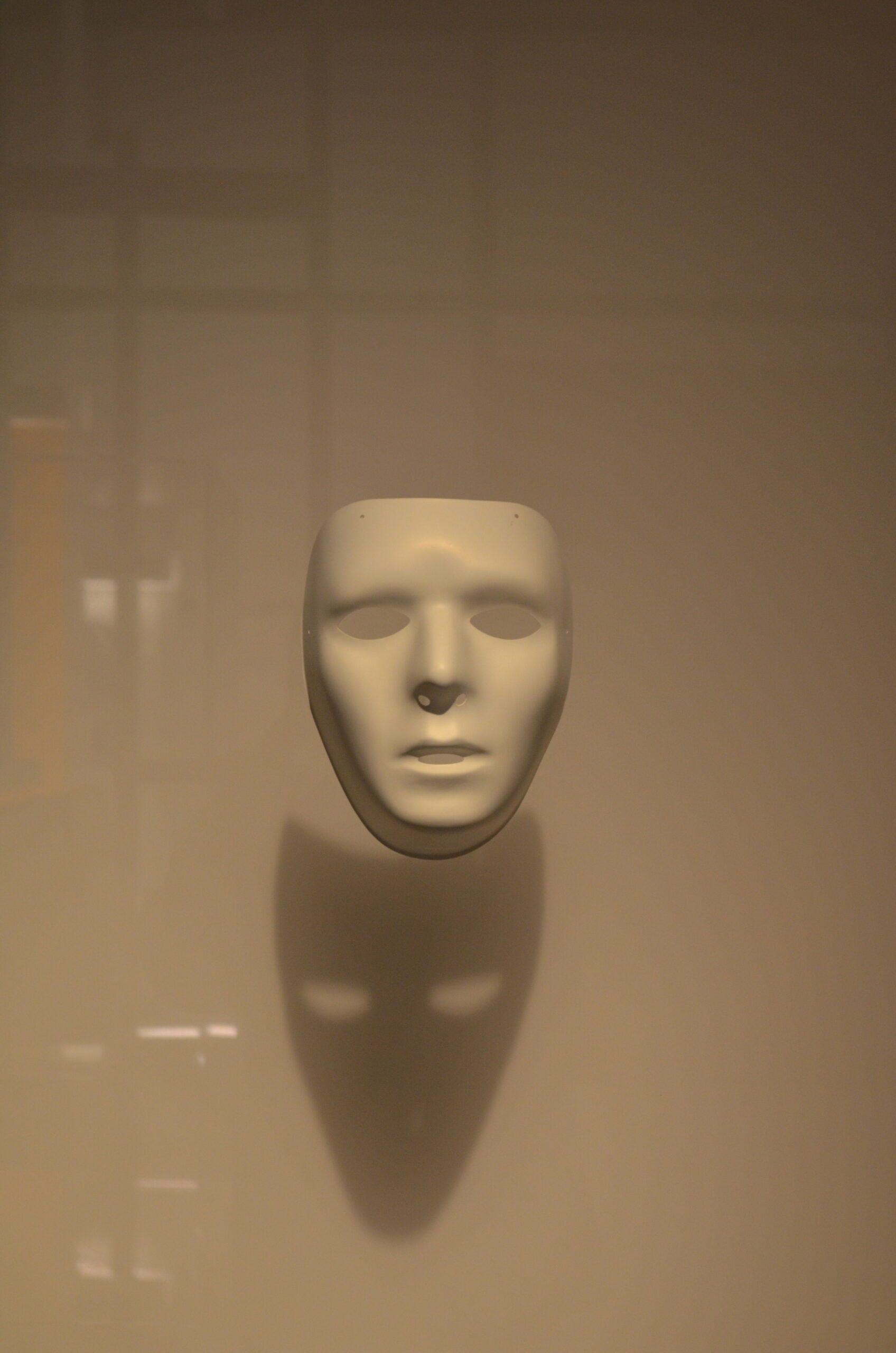

Featuring 15 international artists, the gallery includes works that let you sleep in a color-changing bed, witness the impact of light, and listen to Artist Liliane Lijn (2023) installing her voice into a head-shaped sculpture to evoke dreams in the Sweet Solar Dreams II, offering a journey into rhythm, sleep, and consciousness.

The calm and soothing effect helped further appreciate the art by emphasizing the colors and lights of the installations and sculptures against the dark backdrop, especially with Helga Schmid’s Circadian Dreams (2019-2020), representing the body’s 24-hour cycle with the circular bed and curtains, changing colors depending on the stage it is meant to depict.

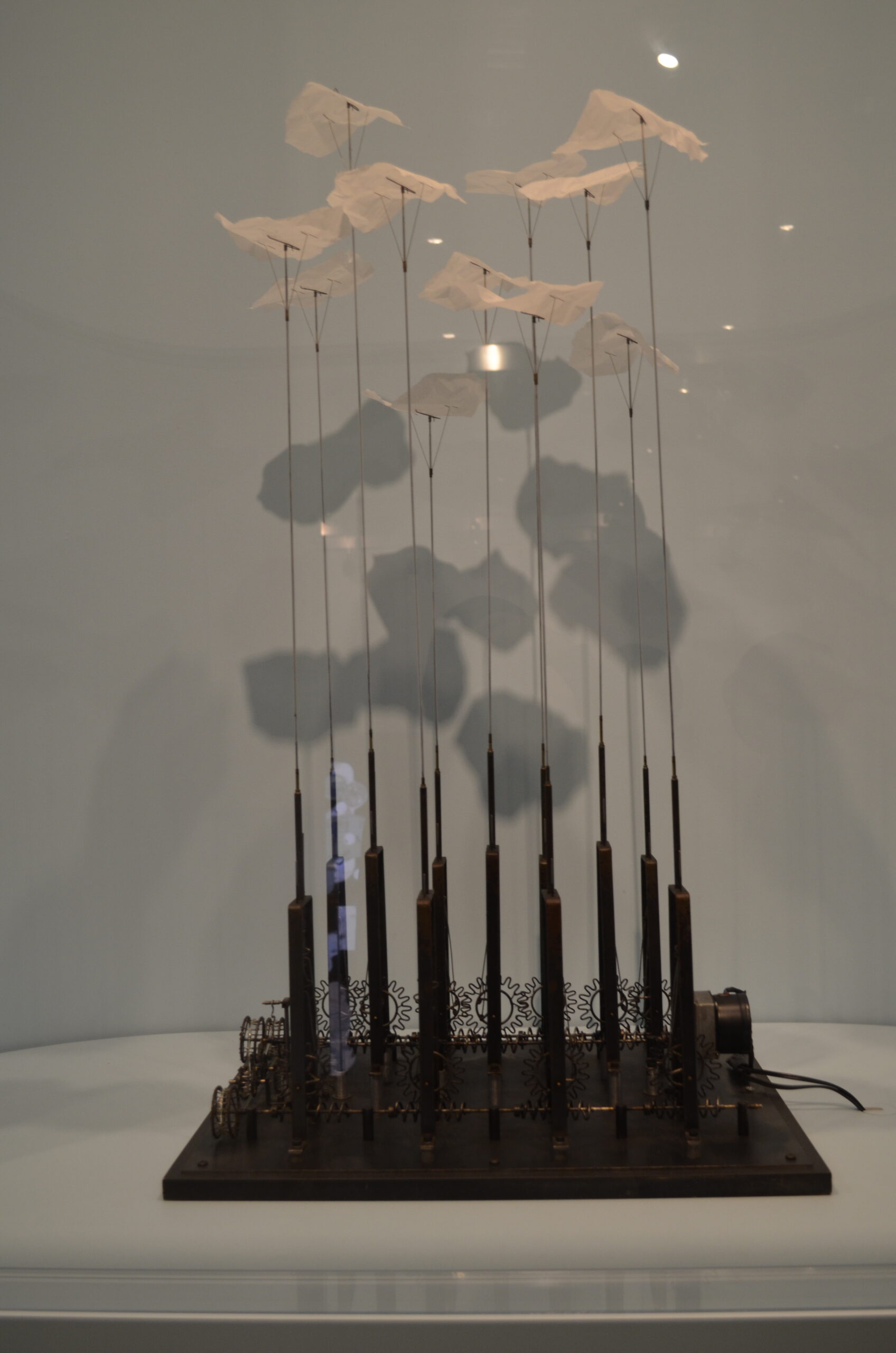

As soon as we left the dimly lit room, we were greeted by stairs that led to a mini-exhibit dedicated to Arthur Ganson, who began creating kinetic sculptures in 1977 and has been featured in numerous galleries and museums throughout the Western Hemisphere.

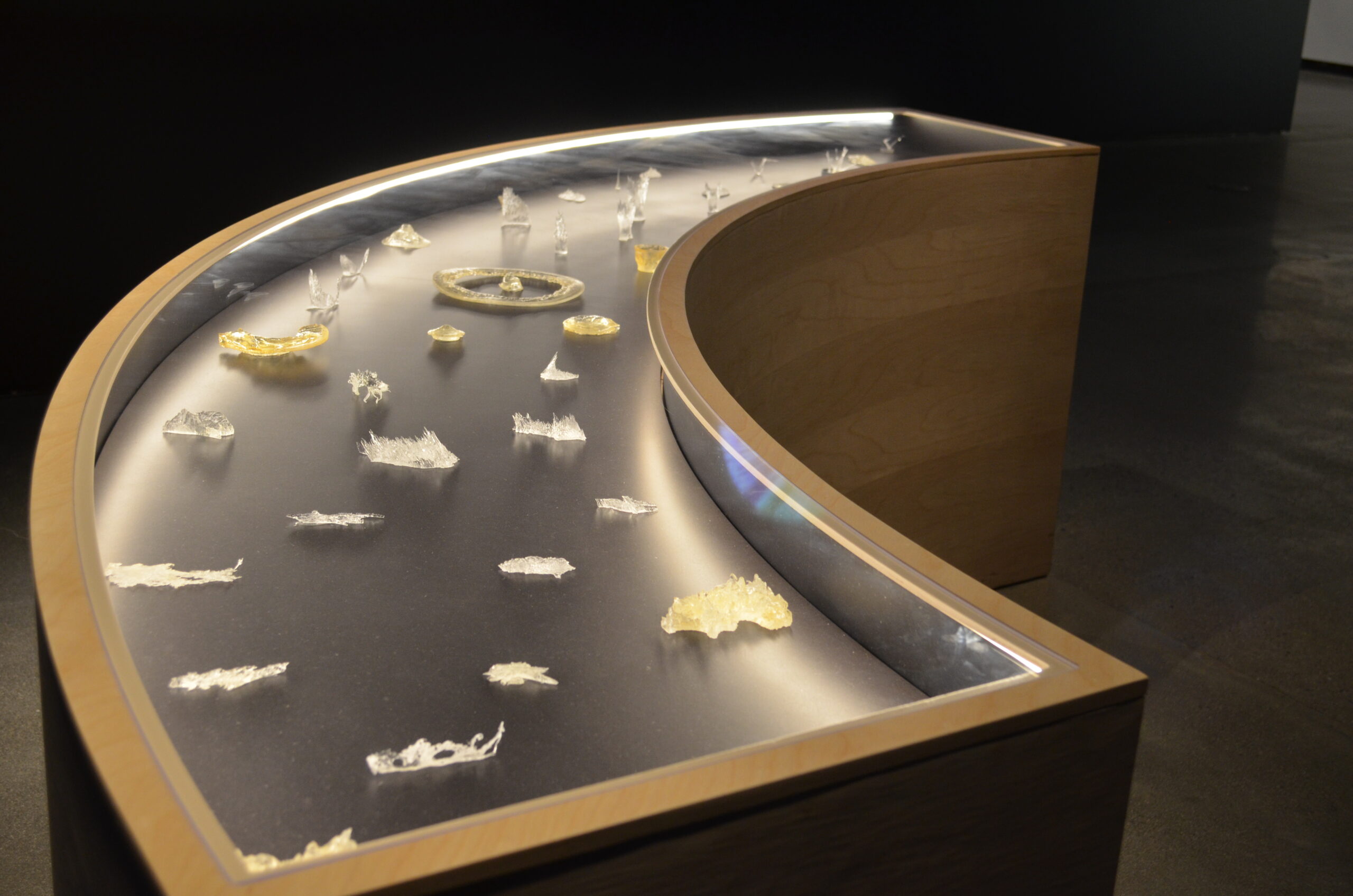

Next came the Cosmograph by DESIGN EARTH in the Martin J. and Eleanor C. Gruber Gallery, blurring the line between fact and fantasy, encouraging reflection on the promises of the New Space Age and its frontier for space exploration.

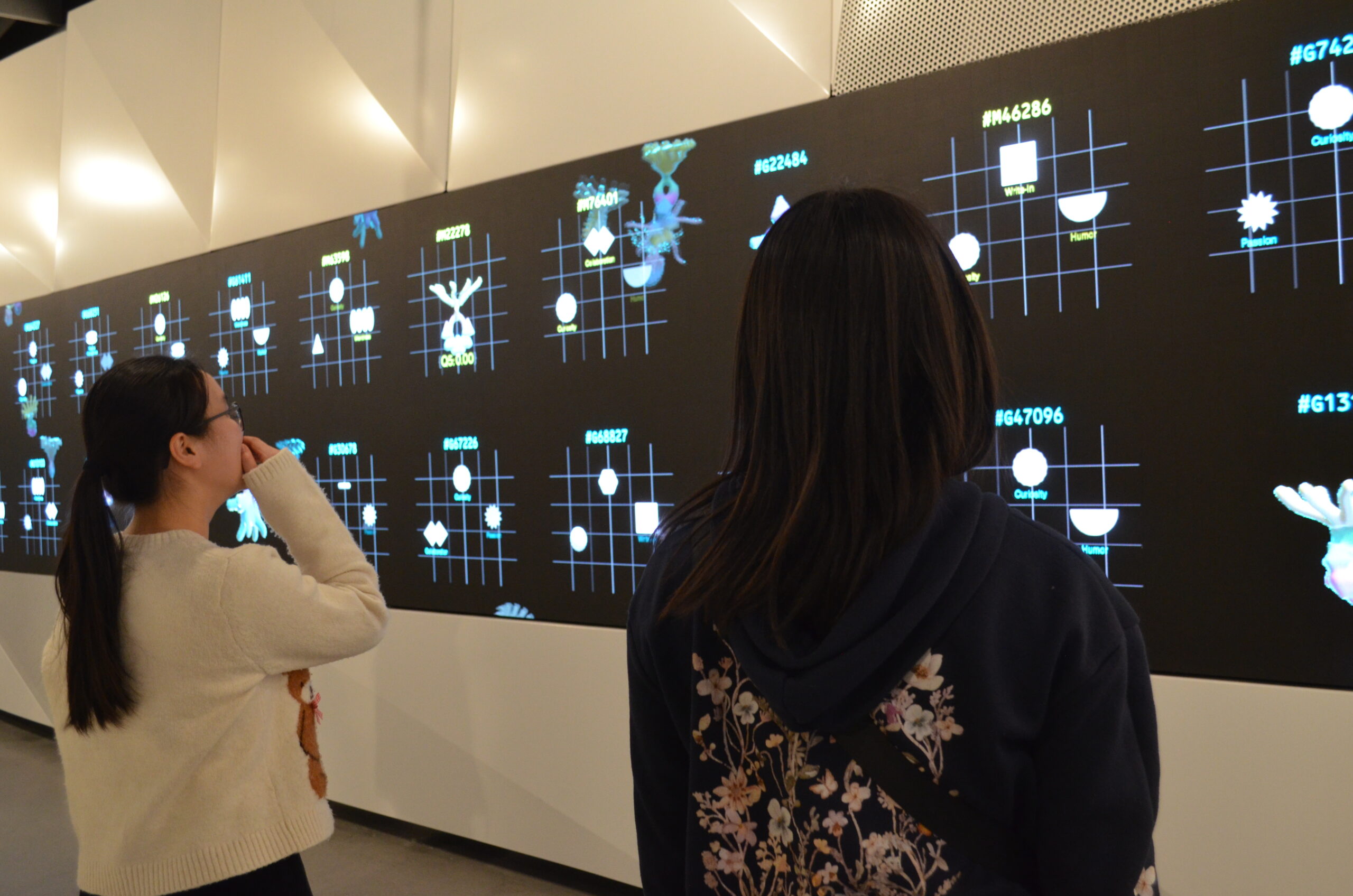

Following the curve of the hall, we reached one of the most fascinating parts of the museum, AI: Mind The Gap. The gallery was very versatile, shifting from displaying robotic innovations to a robot called Jibo to having various philosophical questions related to the technology, such as who gets to decide the truth online, or if AI should have the power it does in today’s society. Near the back, there was a game based on identifying real vs fake videos and images, and students had a great time interacting with it.

The most attention was paid to Jibo, who held eloquent conversations with the speaker and easily switched from one student to another, and the poem generator, where AI and an individual could compose a poetic piece before submitting it into a realm where thousands of others existed. As our poem was processed, we could see it moving up the screen’s arch and over our heads, joining the other literary works.

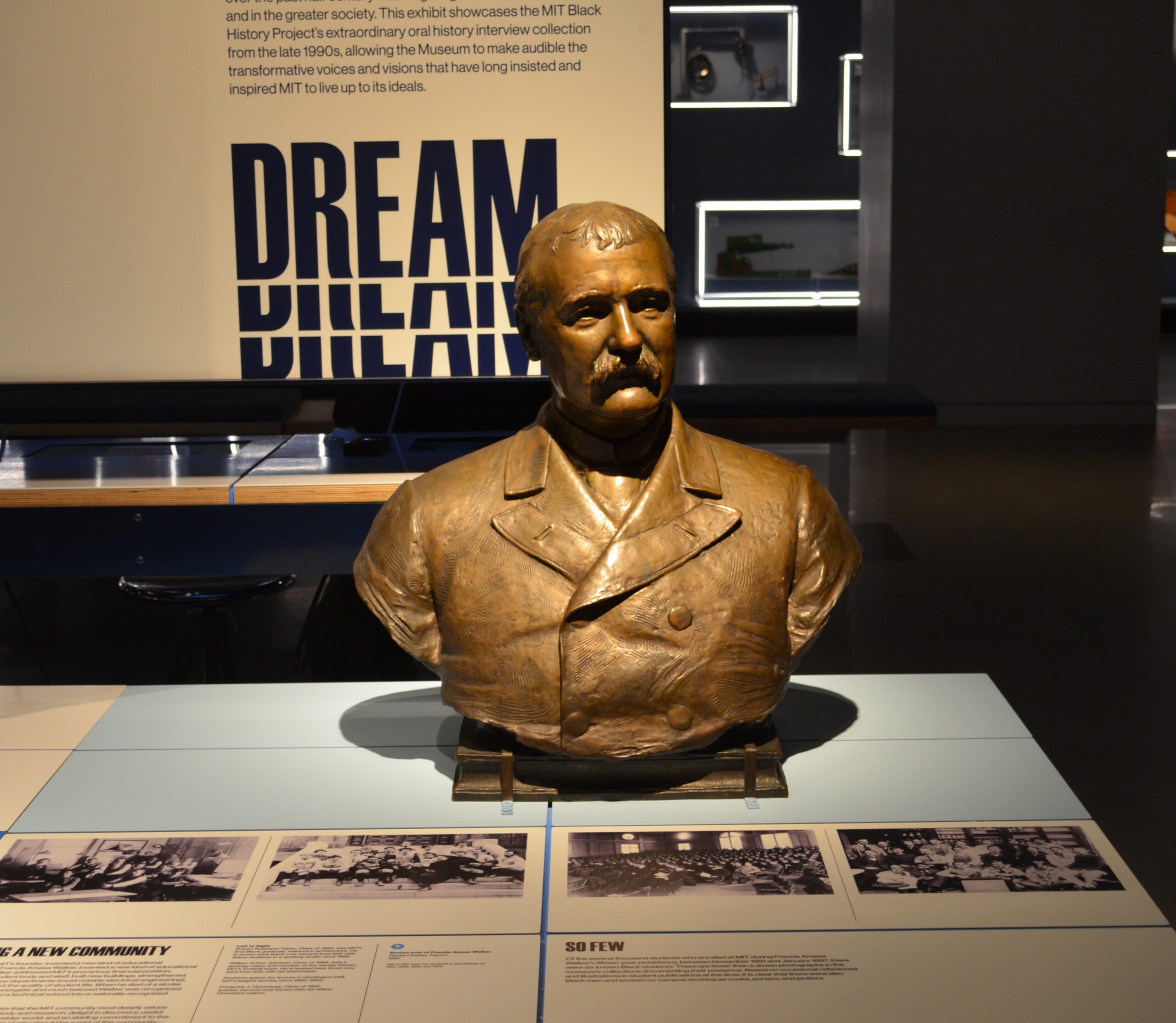

Continuing down the hall came the exhibitions: MIT Collects and the Monsters of the Deep: Between Imagination and Science. MIT Collects is an ongoing display based on storytelling through artifacts, with each section using objects to narrate MIT’s history and research culture. Not only does this illustrate the institution’s contributions in the field, but it also connects past innovations with current ones.

The Monsters of the Deep briefly transported us to an art gallery, where we were surrounded by enclosed walls covered with sea creatures on vintage paper, framed. The exhibit portrays how people tried to understand mysterious sea creatures in the 16th to 19th centuries, depicting how whales and other marine animals were once imagined as terrifying monsters, but gradually recognized as real mammals through careful studies, underlining the connection between science and imagination.

The final two areas toured were Made to Measure—a glass wall containing tools and instruments humans have used to quantify the world, including something as simple as the ruler—and Future Type, presenting how artists and designers use computer code as a creative medium.

While education often focuses on answers, our experience highlighted something different: the most valuable part of the visit was not what we saw, but what we were encouraged to question. As we left the museum to take the train back to Malden, we found ourselves looking beyond surface-level information, assumptions, and biases; instead, we were ready to put our thinking caps on and ponder the possibilities hidden within each display.